The power of small, structured steps

What supervisors can learn from Ohtani and "maximal agentic decomposition"

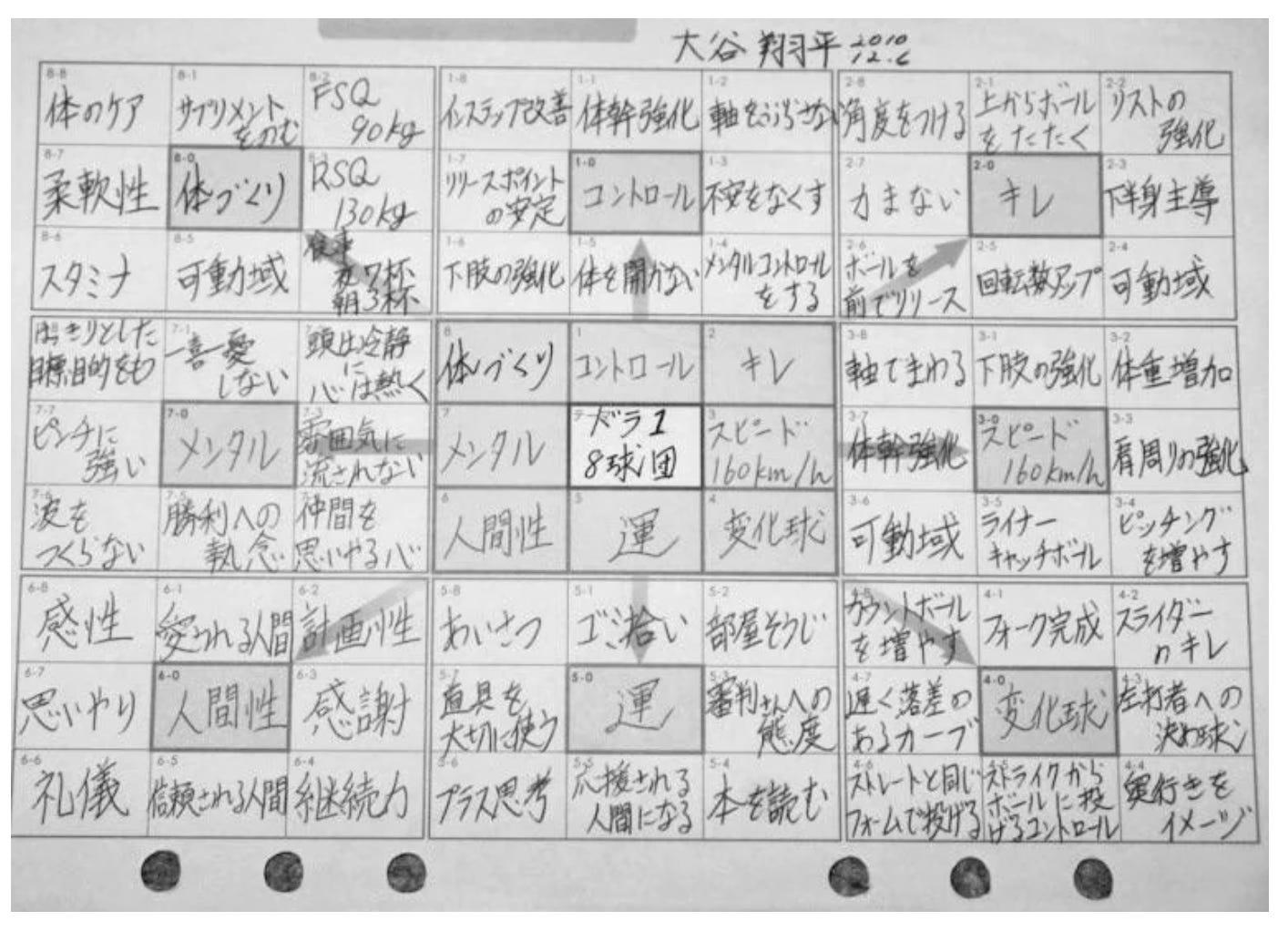

When Dodger’s superstar Shohei Ohtani was a sophomore in high school, he filled out this chart:

It is based on a self-improvement framework called the Harada Method. Translated into English it reads:

The methods breaks down an extremely ambitious goal — “Get drafted 1st overall” (in yellow) — into eight components surrounding it— Body, Control, Speed 100mph, Karma, etc. And then each component is further broken down into eight actionable steps. While getting drafted 1st overall may seem out of reach to a high schooler, each step — “be[ing] considerate to teammates” and “pitch[ing] more” — is imminently doable in day-to-day life.

The structure connects a challenging goal with achievable actions and gives daily discipline a shared purpose.

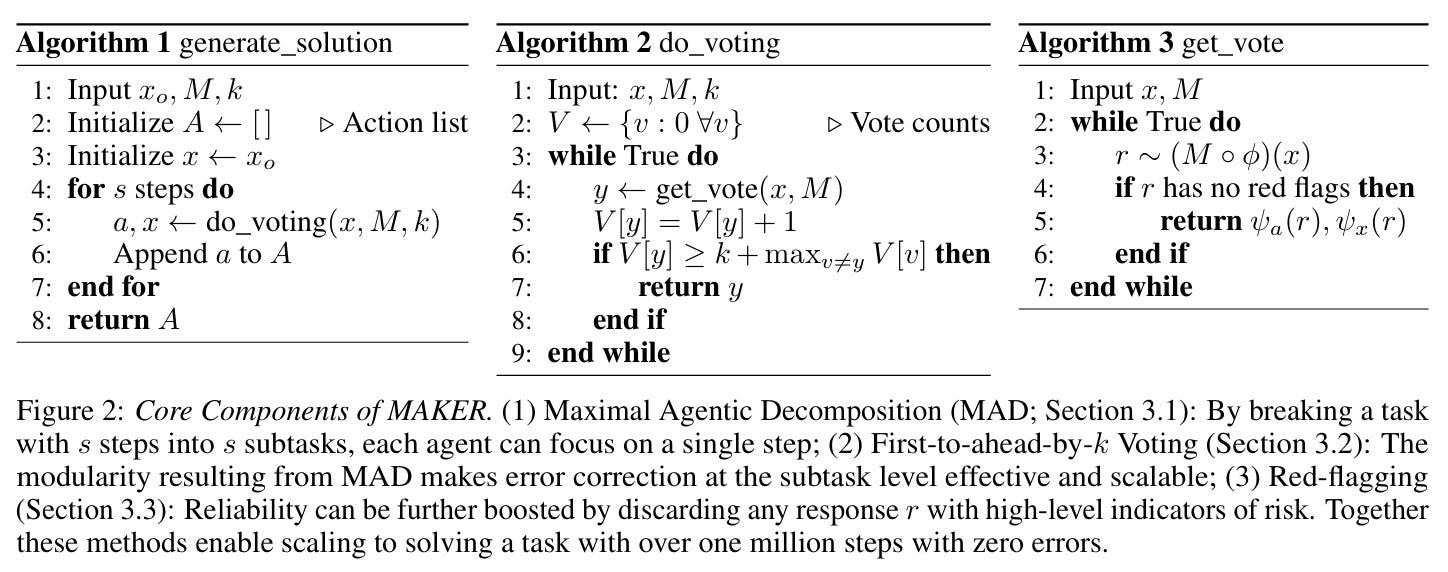

While this image was making the rounds online recently, AI researchers at Cognizant released a paper titled “Solving a Million-Step LLM Task with Zero Errors”. They note:

Technological achievements of advanced societies are built on the capacity to reliably execute tasks with vast numbers of steps… [T]he precise execution of detailed plans and policies is critical to producing high-value outcomes and maintaining societal trust, as the impact of an error in such tasks can range from inconvenience to economic harm to physical harm to death.

In other words, LLMs that hallucinate only 1% of the time will fail after only 100 steps of a many-step task. Even if LLMs were to improve and drop that rate to 0.1%, there would be failure after 1000 steps. Significant undertakings can involve tens of thousands or millions of steps. The researches believe this imposes a limit on our ability to rely on LLMs to do big things.

Their solution is to break ambitious tasks down using “maximal agentic decomposition.” Rather than continuing to build and rely on ever bigger and smarter LLMs, they propose using a set of narrowly focused agents, each able to do a discrete subtask well, subjected to frequent error correction, and closely monitored for correlated errors.1

Using this method on the Tower of Hanoi puzzle, they were able to execute a million step task with zero errors, performing considerably better than o3-mini, Haiku 4.5, Deepseek R1, and Llama 3.2.

Implications for supervision

The concept of doing-small-things-well-to-achieve-larger-goals is not new. Toyota famously revolutionized auto manufacturing by implementing the kaizen method of continuous improvement through small, incremental changes in processes and systems.

What’s different about the Ohtani and Cognizant examples is the structure imposed on the small steps. Ohtani used the Harada box, while Cognizant used micro-agents.

What if these methods were applied to banking supervision?

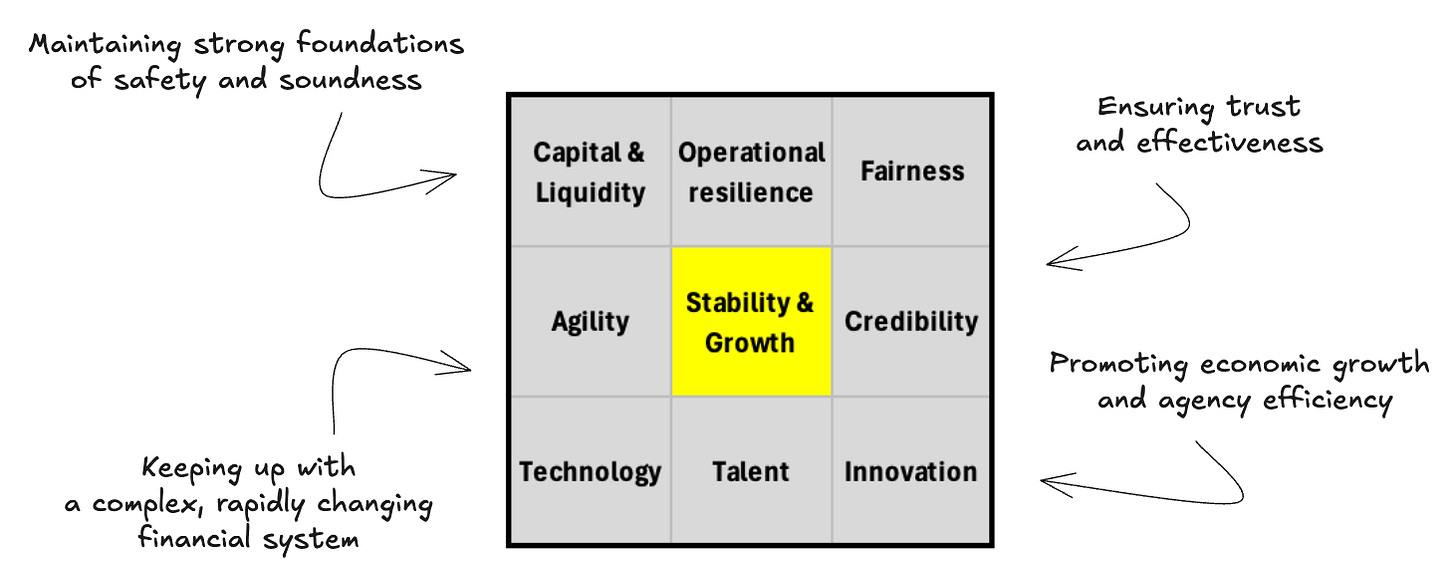

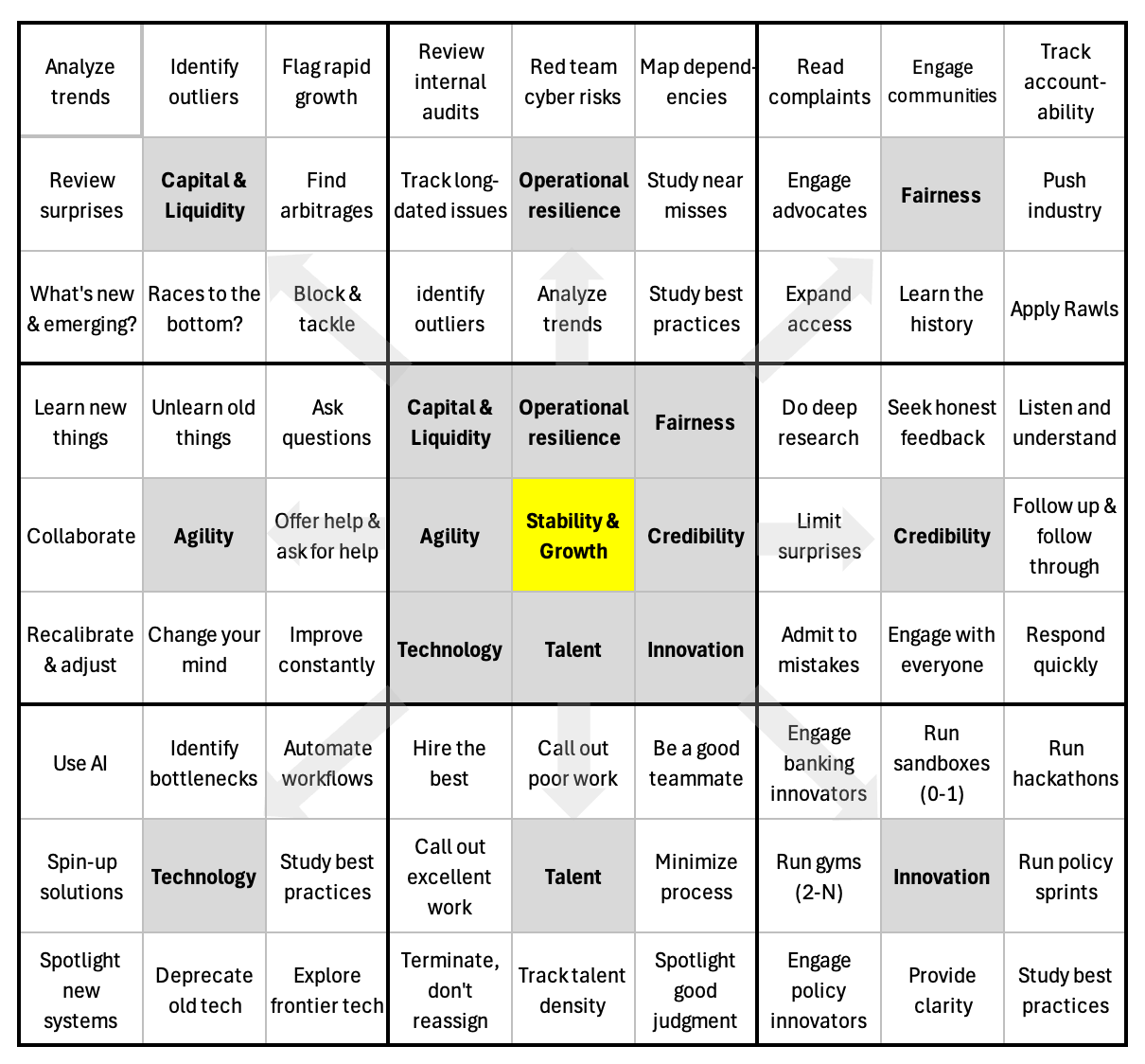

We can start with the center Harada box. Whereas Ohtani’s ultimate goal was “To get drafted 1st overall,” the mission of supervision is to ensure that the banking system operates in a safe and sound manner. In today’s environment, many agencies also have competitiveness and economic growth as a secondary objective, either explicitly (UK) or implicitly (EU, US). Thus, the combination — “stability & growth” — seems like a good center box.

What should the eight supporting components be? Looking ahead, my sense is that the financial system is going to continue to evolve rapidly, that agencies will face sustained pressure to grow and foster innovation, alongside materially tighter budget constraints, and the public will continue to expect stability to be safeguarded. If so, the following offers a plausible starting point.

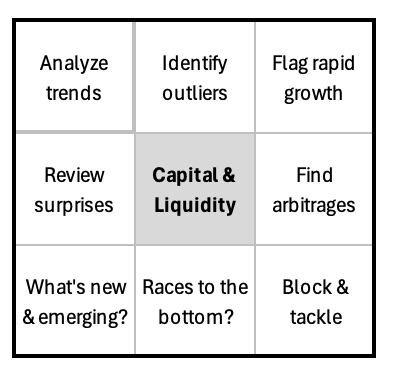

To implement each of the eight components, I took the maximal agentic decomposition approach and tried to identify discrete sub-tasks that could be executed and managed in some way, e.g., amenable to “error correction.”

For instance, I broke the Capital & Liquidity component down into a set of eight habits, things that could conceivably be done by small teams of supervisors or even individual supervisors augmented by AI agents:

Initially, I had listed out tasks and functions of capital and liquidity supervision, like stress testing, horizontal examinations, etc. But I realized that I was just fitting existing org structures and programs into the Harada boxes, which doesn’t add any value. Ohtani’s boxes are powerful because they lay out things he could do every day, that if they became regular habits would help him reach his goals.

I took a similar approach to the other components. Zooming out, my first preliminary draft of a complete Harada box for supervision looks like this:

If a supervisory agency were to follow this chart (or an improved version of it), would the agency be materially more successful in achieving stability & growth? Or would it simply cause confusion amongst staff and create friction with existing priorities? How would this have backtested on the 2023 banking turmoil or the 2008 financial crisis? Which tasks or habits would be most challenging to sustain? Why? Which ones would have the greatest impact on stability? Which ones on growth? Etc.

I am interested in readers’ thoughts on these questions and in alternative Ohtani/Harada boxes for supervisors.